![]() Posted by Cameron Francis

on

24 May , 2016

in

News Uncategorized

Posted by Cameron Francis

on

24 May , 2016

in

News Uncategorized

Welcome to Website Speed is a Ranking Factor: Step Up Your Speed from Snail to Cheetah, part two. In the first part we looked at how you can use a built-in feature in your desktop browser, Developer Tools, to look at what files are making up the biggest parts of your site.

Now we look at what else you can do with the Network tab.

Compression

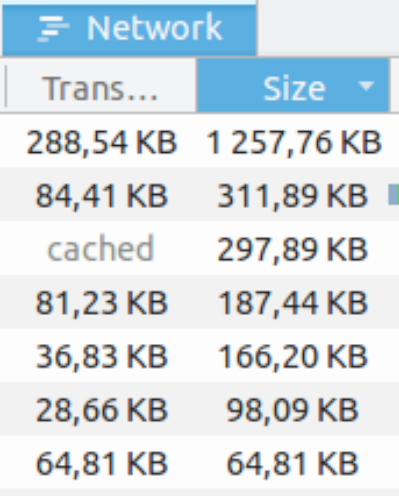

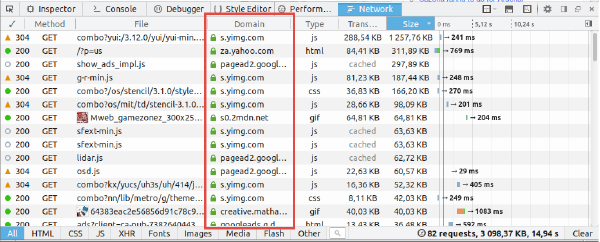

As we mentioned, there are two file sizes shown in the Network tab printout. The first is Transferred and the second is Size.

Transferred literally means how much was sent over the pipe, so in the first example above around 288 kilobytes of information was sent to your browser for the respective file. However, when the file got to us it was in compressed form and expanded to its full size of about 1.2 megabytes.

In order to minimise transition times, something called a Compression Algorithm is used to make things smaller during transit. It’s a clever trick developed by nerds through the ages to write the same message in different forms.

It has its limits: to compress something, and to decompress (turn it back to its original form) takes time, and you can’t shrink things indefinitely.

Certain files, like those containing text, shrink well (JavaScript and CSS are both made up of text). More on this later. Others don’t compress as well, like images.

It’s worth trying to understand why.

As I mentioned, compression is about representing the same thing in different ways. So I could say that

is the same thing as writing

If I were sending a message to someone who understood what I meant by x6 then the second version would be a shorter form of the same message, and in turn I’d use less paper. Really, that’s how it works.

Like I said at the end of the first part, computers and all the clever things that make them up really aren’t any more complicated than, well, anything else …

Anyway, it turns out there are many ways of representing the same messages, and it all turns on smart, interesting ways of recognising patterns. For example, if I wanted to send this message:

I could very well write it as

as long as whoever was reading the message agreed to the format of dots meaning “all the numbers in between”.

Pretty much the core of all compression in the wild uses the first technique – looking for repeated symbols. So to compress an image the technique used in your browser is to look at sections (in fact lines) of equal colour and write them instead as black square x10 (or whatever).

The point I’m trying to make is that there are four things you need to understand when it comes to compression and the speed of your website:

- Compression makes things smaller and thus faster to transmit

- There are various compression techniques (algorithms)

- These have different compression sizes (make different files smaller or bigger) and also loads (use more time to decompress)

- There is a limit to how much you can compress files, and this depends on the file type. e.g. text files like JavaScript and CSS compress better

That’s a lot of points.

It’s a lot to take in but it’s important to understand. Compression is used all over the web to speed things up.

What we see here in the Network tab of Developer Tools is a read-out of the compression used automatically between your browser and the machine sending the file (server). When the file first makes its way to your computer / browser, there is a discussion about what methods are available to make transmission quicker, i.e., like the x6 encoding we used above.

You can read up all about it if you google “HTTP compression” (though from my brief glance the current state of the Wikipedia article isn’t very straight forward).

This is an involved topic so let’s go through it once more.

The Network tab in your browser’s Developer Tools shows all the traffic making up the website you’re viewing. Each line is a file that has been transferred, such as an image or some CSS.

The columns show details of the transfer, like how long it took to transmit and the type of file. Two of these columns show the size, one the compressed size and the other uncompressed. The compressed size is how big a message what transferred, i.e. this number determines the speed of transmission.

So for example, if your customer is sitting on a 10Mbps ADSL line and the compressed file size comes up as 10 Megabytes then it should take 8 seconds for them to download it (because Mbps is mega-bits per second and there are eight bits in a byte… :/). And finally, the compressed size may be different on different browsers because of the differently supported compression algorithms (though my guess is not that often – the major browsers tend to have the same feature set).

Now if you understood all that, well done. That was some pretty high-up geek speak.

Timing and Origin

We started with file sizes. Then we looked at the two different size values – compressed and uncompressed. Now we need to look at something else – where the files are coming from, and how long they actually took to download.

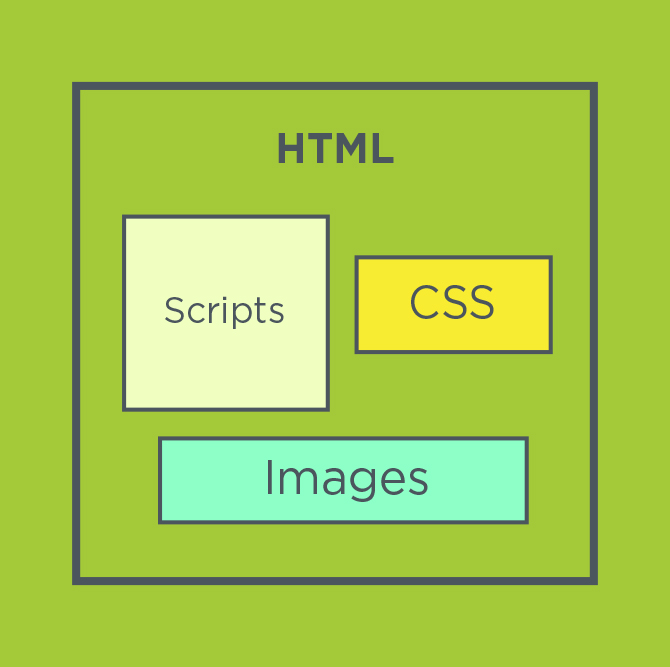

I suppose it’s safe to say whoever is reading this knows about HTML. HTML (as you probably already know) lays out the structure of a webpage. It determines what images, text and libraries are included, where-as CSS says how they should be displayed.

Physically HTML is a block of text, with special markers used to include the images and libraries.

So images and libraries (and CSS) aren’t literally included – they’re references elsewhere. And these references can point anywhere including another site.

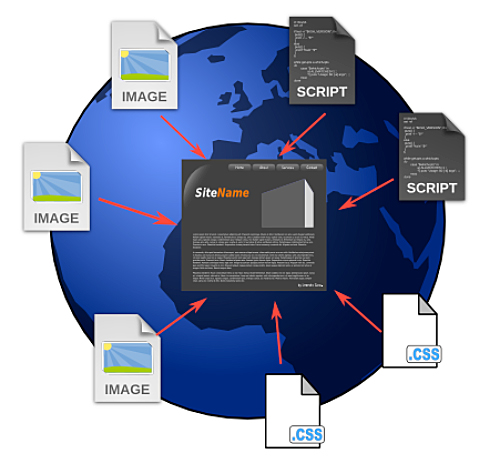

So all web pages are, literally, an amalgamation of files from all across the globe.

That’s what the Domain column means – which web server the particular file comes from. So you can see that yahoo.com has their own machine for serving images – yimg.com – which we can see several times (I’m assuming yimg stands for Yahoo Images).

This is where timing comes in.

The origin affects the download speed, partly because the computer can be slow or overworked, but mainly because of where it is.

If it’s in China and the user is browsing the internet in South Africa then there’s going to be a delay getting the file(s) down. It’s the same principle as the post office – if it’s further away it takes longer to arrive.

Finally, it’s important to note that the times you see aren’t necessarily stable, i.e. they could change dramatically. This is because every trip a file takes to get to you is random.

Much like how a postman can take different routes each day to deliver packages, files on the web burrow their way through the net on different paths each time they travel. And one of these paths might have a roadblock.

This is why normally fast websites can, on occasion, have a slow moment. It’s easy enough to get around this when looking at your own site, though – just refresh the page (and hence the timing values) once or twice.

Status

One more column before we end off.

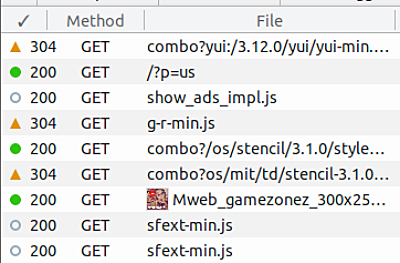

The Status column (indicated by a tick) shows what’s called the HTTP Status.

This is how the file transfer went. It says things like “I had the file and sent it and all seemed fine” (200) and “Well yes I have that file but there’s no need for me to send it because you’ve gotten it from me already!” (304) and “The file you’re asking for is not on my computer!” (404).

It’s just a number that says something specific. The three I’ve mentioned, 200, 304, and 404 are the most commonly seen (and there are many others. Use Google).

But the point I want to make is about 304, “Not Modified”. You will see it often when you use a tool like the one we’re looking at.

The web is built by a lot of really smart engineers who work hard trying to make it efficient. So if you don’t need to do something twice you shouldn’t! If you visit two pages on the same website and they use the same image in each then why waste time and resources downloading it more than once?

So when you see 304 it means the file wasn’t actually downloaded – all the happened was your computer and the one far away had a very short conversation about said file, which is normally super quick.

Speed and the Great Green Light

What this all adds up to is, well, the Internet – a collection of computers tied together in a network of connections, talking to one another in messages, streaming files to each other, and trying to agree on what to do next to serve their fleshy masters.

What they send to each other is HTML, CSS, JavaScript and images, and the language they use is HTTP. And it’s the Network tab of Developer Tools that lets you peer into the conversation.